|

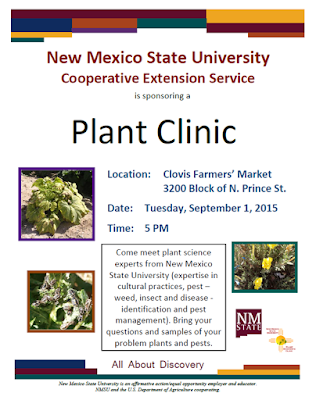

| Bacterial leaf spot on pumpkin leaf. Note the yellow halo surrounding the dark lesion. (Photo: NMSU - PDC) |

Bacterial Leaf Spot of Cucurbits – Bacterial leaf spot of cucurbits is

caused by the bacterium, Xanthomonas campestris pv. cucurbitae. This disease

causes sporadic losses in cucurbit crops grown in temperate climates. In New

Mexico, the disease is not common, but can occur when warm, humid conditions

are persistent. The disease attacks a number of different hosts including

pumpkin, cucumber, gourds, and summer and winter squash.

Symptoms may

appear on both the foliage and the fruit. On the foliage, the disease causes

small somewhat round water-soaked lesions on the underside of the leaf. A

yellow spot appears on the upper leaf surface. In a few days, the spots turn

brown with a distinct yellow halo. The appearance on fruit is variable and

depends on rind maturity and how much moisture is present. Initial lesions are

typically small, slightly sunken, mostly round spots with a tan to beige

center. As the spots enlarge (reaching up to 15 mm in diameter), they become

noticeably sunken and the rind may cracks.

|

| Bacterial leaf spot lesion extends into the seed cavity (Photo: N. Goldberg, NMSU-PDC) |

|

| Bacterial leaf spot on a white pumpkin

(Photo: J. French, NMSU-PDC) |